If you write lines that convey the sense of words in a rhythm we love to sing, you’ve made something unforgettable! That powerful double punch when songwriters harness the natural rhythm of words with their meanings means lyrics can stick in our memories forever.

That’s because any word in English with two or more syllables has its own inherent rhythm or pattern of stress.

Some syllables are stressed more strongly (/) than their ‘weaker’ wordmates (x). Like butter. The first syllable but- is more strongly stressed than the second -ter. Same with the words winter and guitar.

/ x / x / x

but – ter win -ter gui-tar

But a word like select reverses that pattern of stress. The first syllable se- is unstressed while the second syllable -lect is stressed. Same with words like control and mistake.

x / x / x /

se- lect con-trol mis- take

This pattern da-DUM is called an iamb derived from Greek meaning ‘to step forth’ while the first DUM-da comes from the Greek-derived word trochee meaning ‘to run’.

In lyrics, pretty much all words or groups of words come in double (duple) rhythms of stress as above or triple rhythms. There are three main types of triple rhythm (yep, with Greek names):

Dactyls (named after fingers and toes with their three joints) – have the stress on the first syllable, like bicycle.

/ x x

bi-cy-cle

Anapests have the stress on the last syllable – the opposite of dactyls, like interrupt.

x x /

in-ter-rupt

And amphibrachs have the stress in the middle, like potato.

po-ta-to

x / x

In speech, syllable stress tends to be less obvious but getting to grips with the rhythm of your lyrics contributes not only to your song’s groove but also the pace at which your ideas unfold and what words you highlight.

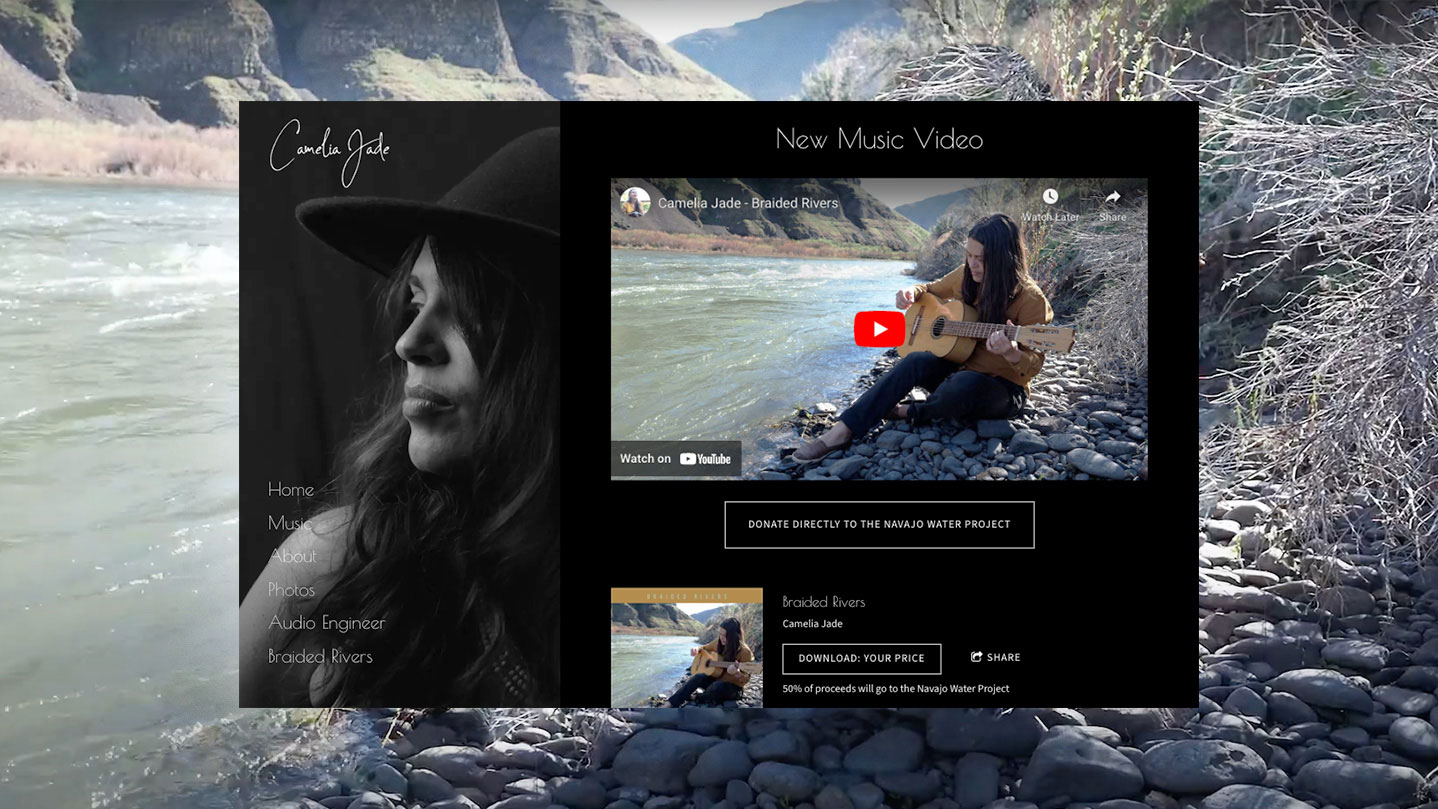

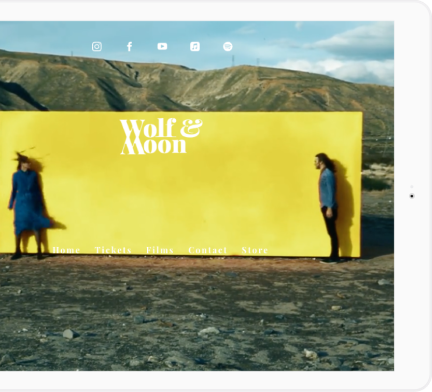

Build a stunning website for your music

Bandzoogle gives you all the tools you need to create your own unique band website, including responsive templates and commission-free selling tools.BUILD YOUR WEBSITE

Sometimes you want words to bubble along lightly, sometimes you want us to wait….and sometimes you want us to lean into a point you’re making. The ability to push the pace of the lyric pace or slow it down means you’re using natural patterns of word stress to create tension… and release.

Here’s some real life examples. The first uses the da-DUM or light-HEAVY stress pattern (iambic).

My da-ddy left home when I was three

And he did-n’t leave much to ma and me

Just this old gui-tar and an emp-ty bot-tle of booze.

It’s from Johnny Cash’s song A Boy Named Sue. The title itself has that da-DUM rhythm

and it’s great for telling stories.

The second uses a triple pattern of stress – the dactylic DUM-da-da or HEAVY-light-light pattern

Pic-ture your-self in a boat on a ri-ver

With tan-ger-ine trees and mar-ma-lade skies.

This is from The Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, and the feel is lighter.

Leonard Cohen used another type of a triple rhythm, the amphibrach or da-DUM-da (light-HEAVY-light) in Famous Blue Raincoat, and the feel deliberately drags.

It’s four in the mor-ning, the end of De-cem-ber, I’m wri-ting you now just to see if you’re bet-ter’

While Britney Spears hits home with the more hard hitting DUM-da or trochee pattern in the punchy Womanizer.

‘Boy don’t try to front I (I) know just (just) what you are are are ‘

So here’s a tip to start with. When you find a title you think will work well, say it out loud and see what natural rhythm it’s got. If you’ve got a one syllable title, what happens when you double it, or triple it. Might be magic!